Way back during the Seminole Wars, a peaceful place in the Central Florida pines became Christmas, every day. Long-ago soldiers named it in 1837, but we owe its role as a North Pole of the South to the history and work of the Tucker family.

We know the story’s beginning thanks to Capt. Nathan S. Jarvis, a U.S. Army surgeon who kept a journal about his war adventures.

Capt. Jarvis arrived at St. Augustine by steamboat in June 1837 and, by mid-December, was with troops deep in the interior of Florida. They trudged past a deserted Seminole town, crossed the Econlockhatchee River, and on Dec. 25, reached a pine barren on what’s now Christmas Creek in east Orange County.

Fort Christmas Historical Park in east Orange County, Florida, includes a re-creation of the original 1837 structure.

The soldiers built a stockade made of upright 18-foot pine logs, sharpened at the top, and named the place Fort Christmas. In just a few days, most of the troops were ordered to move deeper into Florida, leaving the fort and the area largely deserted until about 1860, when John R.A. Tucker and his family settled nearby.

The only means of travel was by oxcart or on horseback, and the Tucker home became a stopping-place for travelers. After the community gained a post office in 1892, a member of the Tucker family was in charge for much of the next century.

In 1916, Lizzie Tucker got the job, taking over from her husband, Drew. In 1932, the mantel passed to their daughter-in-law Juanita, who stayed on the job for more than 40 years. Juanita Tucker was 101 when she died in 2008, then the oldest resident of Christmas and the one who had done the most to put it on the map.

“She got the community together. She was good at that,” her son Cecil A. Tucker II said after her death. “Anytime that people had a need, she would find some way or someone to help out.”

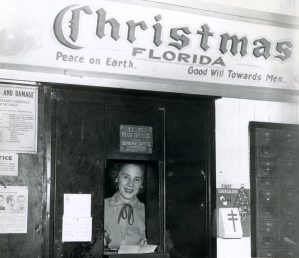

The old Christmas post office (the same building shown in the picture of Juanita Tucker at the window).

“The post office was always the one place people could count on to get information and help,” Juanita Tucker once said. “That’s what made it such a wonderful job. There were so many ways I was able to help people that had nothing to do with the post-office business.”

About 1937, the Tuckers moved postal headquarters to a one-story white-frame building with a small porch. When the highway through Christmas was widened to four lanes, that 1937 post office was moved from the south side of the road to the north side, where it still resides in a peace garden at Colonial Drive (S.R. 50) and Fort Christmas Road.

A mosaic at the peace garden in Christmas, Florida. It’s on State Road 50, about 20 miles east of Orlando.

Asked what he would most like folks to know about the community of Christmas, Cecil Tucker didn’t mention his family, often called “legendary” in Florida ranching lore. In a state where people consider themselves old-timers if they’ve been here since 1960, the Tuckers have a hundred years on them.

For him, his family’s legacy is all about the spirit of Christmas, in both global and local aspects.

“This community has a spirit of helping each other,” Tucker said. “If any place has the Christmas spirit, this is it.”

Christmas, and the Fort Christmas Historical Museum, is 20 miles east of Orlando, en route to Kennedy Space Center, Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge, and Canaveral National Seashore in Titusville. See http://www.nbbd.com/godo/FortChristmas/

In one of my favorite childhood photos, a friend and I are playing dress up. She’s princess-elegant in a long dress, but I’m swathed in a scarf and shorts, a smiling child with a too-curly perm trying to channel some Indian elephant boy out of Kipling. Now I think perhaps I was channeling my inner Richard Halliburton. Although once a renowned emblem of travel adventure, my Halliburton has nothing to do with the aluminum travel cases of that name, or with the multinational Halliburton Corp. He has to do with the worlds he opened for me and many other children through his Complete Book of Marvels. First published in 1941, it has long been out of print but still rates stellar reviews on Amazon.com. “My favorite book of all time,” notes one, in a thought echoed by others.

In one of my favorite childhood photos, a friend and I are playing dress up. She’s princess-elegant in a long dress, but I’m swathed in a scarf and shorts, a smiling child with a too-curly perm trying to channel some Indian elephant boy out of Kipling. Now I think perhaps I was channeling my inner Richard Halliburton. Although once a renowned emblem of travel adventure, my Halliburton has nothing to do with the aluminum travel cases of that name, or with the multinational Halliburton Corp. He has to do with the worlds he opened for me and many other children through his Complete Book of Marvels. First published in 1941, it has long been out of print but still rates stellar reviews on Amazon.com. “My favorite book of all time,” notes one, in a thought echoed by others.