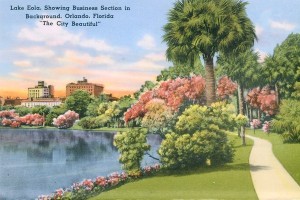

It’s April 1, and I’ve just returned from a walk at Orlando’s Lake Eola Park, which offers excellent people- and creature-watching. Folks stroll along with anything from a pomeranian to a python. But on this very April day a few years ago,I stumbled on the strangest pet story I’ve ever heard from Central Florida’s past.

It was just about twilight when I found myself walking at the park behind a stooped, white-haired man with a long beard. Behind him on the pavement were what first appeared to be five flat, dark, oval stones. Ack! They moved. They looked like palmetto bugs, our Florida roaches. Impossible. The man turned and fixed me with a gaze that would melt butter.

“Whatever you do,” he said in a low voice, “be careful where you step.” I could only stare. When he stopped, the line of dark shapes behind him stopped, too.

“You see,” he said, “these are true descendants of Palmetto Pete, the biggest bug ever to come out of Florida. They don’t hatch ’em like Pete any more. He was a star. Palmetto Pete’s Scrambling Circus, Pappy called it. People loved it.”

“But, roaches?” I said, thinking of those creatures that plague the recesses of my old kitchen.

“See, this was back in the 1920s,” he went on. “People were flocking into Orlando like bees to honey.” Or like roaches, I thought.

“My pappy had heard about these flea circuses at fairs up north. He figured we had almost as many of them palmetto bugs around our yard as an old dog has fleas. They were a whole lot bigger, too, and strong!

“Pappy hitched those critters up to a tiny wagon they pulled around a cute little circus arena he built for them. They weren’t all smart like Pete , of course. Pappy knew Pete was special the minute he saw that bug sauntering across our kitchen floor. My mammy was just about to give Pete a smack with a rolled-up newspaper, but Pappy said, no ma’am, that bug’s gonna make us some money.”

I shivered. “So what happened?”

“Oh, Pete was a wonder,” the old man went on. “Could catch a tiny trapeze, ride on the back of a little dog; he could even fly. Pappy was making money hand over fist with his circus. There was just one problem: That bug was bad to drink. This was during Prohibition, and Pete began lappin’ up that moonshine. That roach just became a disgrace. He started falling off that tiny dog’s back, and talking real rude to the lady bugs. One sad day Pappy found him on his back with his legs up in the air.”

A tear dropped onto his worn jeans. And then the old man gathered himself up to walk away, but before he did, he leaned over and whispered one more thing to me.

“Dearie,” he said, “Happy April Fool’s Day to you.” I send the same greeting to you, gentle readers. April 1 is a fine time for foolery. But, we must admit, from what we know of Florida, big Pete might really have existed.

P.S. I looked up ways to battle roaches in Florida, hoping to add something useful to this tale, but found so many online that I opted for this instead: Baton Rouge blues master Silas Hogan’s version of “I Got Rats and Roaches in My Kitchen.” Not Florida, but close enough. http://bit.ly/1jUoTtJ

In one of my favorite childhood photos, a friend and I are playing dress up. She’s princess-elegant in a long dress, but I’m swathed in a scarf and shorts, a smiling child with a too-curly perm trying to channel some Indian elephant boy out of Kipling. Now I think perhaps I was channeling my inner Richard Halliburton. Although once a renowned emblem of travel adventure, my Halliburton has nothing to do with the aluminum travel cases of that name, or with the multinational Halliburton Corp. He has to do with the worlds he opened for me and many other children through his Complete Book of Marvels. First published in 1941, it has long been out of print but still rates stellar reviews on Amazon.com. “My favorite book of all time,” notes one, in a thought echoed by others.

In one of my favorite childhood photos, a friend and I are playing dress up. She’s princess-elegant in a long dress, but I’m swathed in a scarf and shorts, a smiling child with a too-curly perm trying to channel some Indian elephant boy out of Kipling. Now I think perhaps I was channeling my inner Richard Halliburton. Although once a renowned emblem of travel adventure, my Halliburton has nothing to do with the aluminum travel cases of that name, or with the multinational Halliburton Corp. He has to do with the worlds he opened for me and many other children through his Complete Book of Marvels. First published in 1941, it has long been out of print but still rates stellar reviews on Amazon.com. “My favorite book of all time,” notes one, in a thought echoed by others.